|

| Corporate pinkwashing in action |

We've all seen them-- the pink ribbons splashed across jackets and water bottles, spatulas and rice cookers. It seems so innocent at first-- most of us have known someone in our lives who has gone through breast cancer. For me, it was my mom. My aunt's best friend who I saw this past Thanksgiving just got diagnosed and is going through her first round of chemo.

Supporting these women is important. For people who have survived other cancers, the pink propaganda splattered across every household item rubs them the wrong way. "Thinking pink" is no only non-inclusive inherently (as campaigns and research routinely prefers white women over others who suffer from breast cancer).

Pink dominates the cancer awareness scene-- but what a lot of people don't consider is who the pink ribbon is actually helping.

Hint: Its not the 1 in 8 women who will be diagnosed with breast cancer (in the U.S. alone).

Of course breast cancer awareness is integral. But as the rates of breast cancer in women keep going up, and we keep spreading "awareness", we have to stop and look at this movement critically. Aren't we past the point where we need to raise more awareness?

Personally, I've known about breast cancer since I was a kid. I've been told I'll need to start getting mammograms early, and to check for lumps regularly. Most women are very aware of the risk, and what to *try* to look out for. Unfortunately, breasts are so diverse that often women have trouble identifying what is abnormal or not.

Awareness is in the past

|

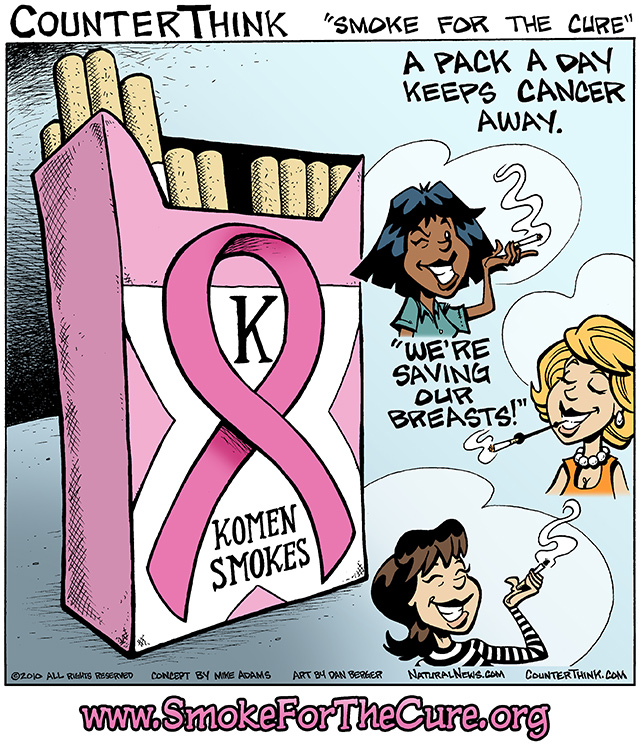

| Political cartoon on the concept of pinkwashing |

Corporate exploitation.

Pinkwashing is a term first coined by Breast Cancer Action. It refers to when a company or organization claims to care about breast cancer by promoting a pink ribbon product, but at the same time produces, manufactures and/or sells products that are linked to the disease. This can be anything from food items with pink labels to fracking companies that use pink screws for their rigs. Its corporate dishonesty and moral deficiency-- and so many people fall victim to it in the name of trying to do some good.

This is exactly why Breast Cancer Action launched their campaign Think Before You Pink-- to try to combat this corporate exploitation.

But is it enough?

When looked at through a critical ecofeminist lens, the plight is obvious. Women are targets and immediate victims of corporate greed-- just like the environment. This deeply connected to what ecofeminism discourse argues-- the corrupt hands of corporate America reaching its grubby hands deep into breast cancer awareness campaigns. Women are the most affected-- all this money that people think is going to women and fighting this epidemic the disproportionately affects women, and all of it is going into the pockets of big business-- more so than any other ribboned cause.

We're just a profit-booster to them.

One of the worst parts is that the people who most often fall victim to this kind of marketing and exploitation are those who have been affected by this cancer epidemic-- survivors, families, et cetera.At Thanksgiving, I overheard a relative explain how they always try to purchase items with the pink ribbon label-- in support of people like my mom.

To take advantage of people's hearts like this should be a crime.

Unfortunately, in corporate America where we love capitalism, its the exact opposite: a good marketing tactic.

|

| Shattering of rose-colored glasses |

So, how do we stop this, or at least make it better?

First, lets shatter the rose colored glasses.

Educate yourself. Before you buy anything with the pink ribbon, research the company. See if any money actually goes to a research organization (Susan G. Komen doesn't count).

Include everyone affected by breast cancer intersectionally-- everyone's voice matters, and everyones experience matters. No two are alike, and breast cancer affects so many people.

Support your loved ones in other ways. We need to stop thinking pink and start thinking human.